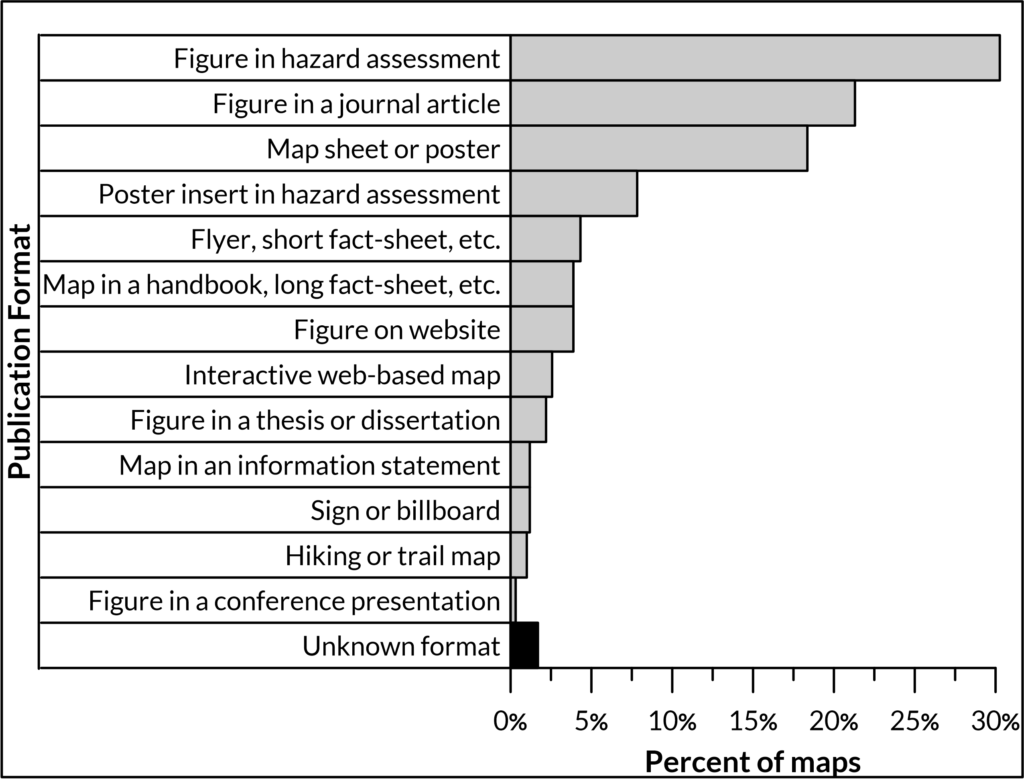

Hazard maps can be classified by their publication format, which is closely related to the map’s intended purpose and audience.

Hazard maps can be formatted as map sheet or poster-style maps, which may be published either as pocket-inserts (e.g. Adams, USA, 1995) in accompanying hazard assessments or as stand-alone maps (e.g. Lamongan, Indonesia, 2015).

Maps may also be published as small-scale figures in hazard assessments (e.g. Galeras, Colombia, 2015); scientific journals (e.g. Vesuvius, Italy, 2017); or websites (e.g. Holuhraun, Iceland, 2015).

Hazard maps intended for public awareness are also commonly featured in short flyers, brochures, fact-sheets, or infographics (e.g. Ambae, Vanuatu) or as images in longer booklets, brochures, or handbooks (e.g. Asamayama, Japan, 2019)

Hazard maps for volcanoes with nearby tourist attractions or hiking trails are sometimes published as hiking trail maps, designed to be carried by hikers (e.g. Kirishimayama, Japan, 2019). These maps often have packing checklists, cell phone coverage maps, and information about evacuation routes.

Other maps may be published as large-scale signs, billboards, or placards, often near the volcano or hazard zones themselves (e.g. Rainier, USA, 2014).

Short-term crisis maps are often published as figures in information statements (e.g. Villarrica, Chile, 2015).

Increasingly, interactive hazard maps are being created that allow a user to manipulate the scale, view, and layers visible on the hazard map and sometimes to search for particular locations (e.g. Sabancaya, Peru, 2019). Interactive hazard maps are published as websites or phone apps.